James Nehring

Great teaching is about engaging people in learning. But in a school system focused on stuffing kids heads full of facts, where is learning - or engagement - to be found? I began my career as an educator in a rural middle school in upstate New York. Many families in town struggled to make ends meet and school resources were limited. Then I moved to a suburban school district near the state Capital of Albany, where families had money and college degrees, and the schools were well funded. There I taught high school. Despite the differences in money and resources, school routines were basically the same in both places. Desks in columns and rows, memorizing facts and formulas, drilling for the next test. I felt stuck in an industrial system that mass processes everything, including children. This was the subject of my first book, “Why Do We Gotta Do This Stuff, Mr. Nehring?”.

Some teachers, like me, wanted more. So did families, (The subject of my second book, The Schools We Have, the Schools We Want). We organized. We made a plan. We advocated. And after several years, we launched an alternative high school with a curriculum driven by questions, lessons connected to real

world problems, and an emphasis on community and service. Students in the Bethlehem Lab School flourished (my third book, The School Within Us). Word spread, and I was tapped by a new public charter school in Massachusetts, with similar ideals, to serve as principal. It was a fuller expression of what we aspired to in Albany and the Parker Charter Essential School gained national notoriety (book four, Upstart Startup). Parker was largely middle class and white. Several of us set out to create a sister school that would serve a more economically and racially diverse community. We launched the North Central Charter Essential School in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. Later renamed Sizer School, it continues to serve a diverse, metropolitan community in a progressive mold.

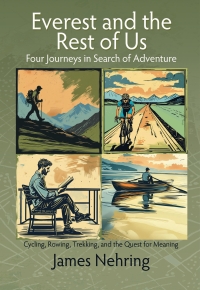

I was growing restless for change on a larger scale. I needed to understand how systems work. So I returned to graduate school to earn my doctorate, studying the history of school reform. I then joined the faculty at the University of Massachusetts Lowell (book five, The Practice of School Reform). There I’ve studied progressive schooling across history and cultures, while teaching and advocating for progressive principles in our undergraduate and graduate programs. Through the United States Department of State, I’ve had the privilege to learn with and from teachers working effectively in communities around the world, sometimes against long odds. My interest in learning has more recently expanded beyond the classroom and schoolhouse (book six, Why Teach? Book seven, Bridging the Progressive-Traditional Divide). I ask, how can each of us achieve fulfillment, what Aristotle called eudaimonia, human flourishing, and what Japanese culture calls ikigai, a life of purpose? I want to understand the ways society constrains human growth and the possibilities for liberation (coming soon, Everest and the Rest of Us).

Some teachers, like me, wanted more. So did families, (The subject of my second book, The Schools We Have, the Schools We Want). We organized. We made a plan. We advocated. And after several years, we launched an alternative high school with a curriculum driven by questions, lessons connected to real

world problems, and an emphasis on community and service. Students in the Bethlehem Lab School flourished (my third book, The School Within Us). Word spread, and I was tapped by a new public charter school in Massachusetts, with similar ideals, to serve as principal. It was a fuller expression of what we aspired to in Albany and the Parker Charter Essential School gained national notoriety (book four, Upstart Startup). Parker was largely middle class and white. Several of us set out to create a sister school that would serve a more economically and racially diverse community. We launched the North Central Charter Essential School in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. Later renamed Sizer School, it continues to serve a diverse, metropolitan community in a progressive mold.

I was growing restless for change on a larger scale. I needed to understand how systems work. So I returned to graduate school to earn my doctorate, studying the history of school reform. I then joined the faculty at the University of Massachusetts Lowell (book five, The Practice of School Reform). There I’ve studied progressive schooling across history and cultures, while teaching and advocating for progressive principles in our undergraduate and graduate programs. Through the United States Department of State, I’ve had the privilege to learn with and from teachers working effectively in communities around the world, sometimes against long odds. My interest in learning has more recently expanded beyond the classroom and schoolhouse (book six, Why Teach? Book seven, Bridging the Progressive-Traditional Divide). I ask, how can each of us achieve fulfillment, what Aristotle called eudaimonia, human flourishing, and what Japanese culture calls ikigai, a life of purpose? I want to understand the ways society constrains human growth and the possibilities for liberation (coming soon, Everest and the Rest of Us).